Copenhagen climate talks deadlocked; Police fire pepper spray, beat protesters; 230 detained

By Charles J. Hanley, APWednesday, December 16, 2009

Climate talks deadlocked as clashes erupt outside

COPENHAGEN — The 10-day-old climate talks ran into disputes and paralysis as they entered a critical stage Wednesday, just two days before President Barack Obama and more than 100 other national leaders hope to sign a historic agreement to fight global warming.

Poorer nations stalled the talks in resistance to what they saw as efforts by the rich to impose decisions falling short of strong commitments to reduce greenhouse gases and to help those countries hurt by climate change. Conference observers said, however, that negotiators still had time to reach agreements.

Outside the meeting site in Copenhagen’s suburbs, police fired pepper spray and beat protesters with batons as hundreds of demonstrators sought to disrupt the 193-nation conference, the latest action in days of demonstrations to demand “climate justice” — firm steps to combat global warming. Police said 260 protesters were detained.

Earlier, behind closed doors, negotiators dealing with core issues debated until just before dawn without setting new goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions or for financing poorer countries’ efforts to cope with coming climate change, key elements of any deal.

“I regret to report we have been unable to reach agreement,” John Ashe of Antigua, chairman of one negotiating group, told the conference.

In those talks, the American delegation apparently objected to a proposed text it felt might bind the United States prematurely to reducing greenhouse gas emissions before Congress acts on the required legislation. U.S. envoys insisted, for example, on replacing the word “shall” with the conditional “should.”

Later, faced with complaints from developing nations about such changes, the Danish leaders of the talks crafted what they hoped would be a compromise text. Even before that was circulated, however, the unhappy nations — the Group of 77 and China — met separately to decide on a position.

“They are unhappy about these texts being handed to them from above,” an African delegate said outside the meeting, speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to talk to the media.

The latest dispute highlighted the undercurrent of distrust developing nations have for the richer countries in the long-running climate talks. But veteran observers said it was too early to give up on the talks, which are supposed to end Friday with Obama and the other leaders approving a final agreement.

“A lot of things are in play,” said Fred Krupp of the U.S. Environmental Defense Fund. “This is the normal rhythm of international negotiations.”

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez echoed the protesters’ sentiments when he told the assembly: “If the climate was a bank, a capitalist bank, they would have saved it.”

There were some steps forward, too. The United States, Australia, France, Japan, Norway and Britain pledged $3.5 billion in the next three years to a program aimed at protecting rain forests. The U.S. portion was $1 billion.

U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said the money would be available for developing countries that come up with ambitious plans to slow and eventually reverse deforestation — an important part of the talks because it’s thought to account for about 20 percent of global greenhouse emissions.

The talks so far have been marked by sharp disagreements between China and the United States, and between rich and poor nations. Still unresolved are the questions of emissions targets for industrial countries, billions of dollars a year in funding for poor countries to contend with global warming, and verifying the actions of emerging powers like China and India to ensure that promises to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are kept.

Addressing the full conference, Swedish Environment Minister Andreas Carlgren, speaking for the European Union, urged the U.S. and China to raise their emissions-reduction targets.

“The world needs more and we are confident that you have the ability to deliver more,” he said of the two countries.

After nine days of largely unproductive talks, the lower-level delegates were handing off the disputes to environment ministers in the two-week conference’s critical second phase.

Connie Hedegaard, a former Danish climate minister, resigned from the conference presidency to allow Danish Prime Minister Lars Loekke Rasmussen to preside as a higher-ranking official at the formal Wednesday-Friday segment involving heads of state and government. She was to continue overseeing closed-door negotiations.

Organizers still hope to break deadlocks that threaten to leave the meeting with no major accomplishments to be presented to Obama, Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao and the other leaders arriving for Friday’s finale.

The lack of progress disheartened many, including small island states threatened by rising seas.

“We are extremely disappointed,” said Ian Fry of the tiny Pacific nation of Tuvalu. “I have the feeling of dread we are on the Titanic and sinking fast. It’s time to launch the lifeboats.”

Others were far from abandoning ship. “Obviously there are things we are concerned about, but that is what we have to discuss,” Sergio Barbosa Serra, Brazil’s climate ambassador, told The Associated Press. “I would like to think we can get a deal, a good and fair deal.”

Governments had weeks ago given up hope of concluding a finished treaty at Copenhagen and aimed instead at establishing a framework for negotiating more formal agreements next year.

Much of the uncertainty in the Copenhagen talks stems from how slowly the first U.S. legislation to cap carbon dioxide emissions is moving through Congress. Passage of a U.S. climate change bill is expected no earlier than next spring — and many other nations are unwilling to make their final commitments until the U.S. does.

A sponsor of that climate legislation, U.S. Sen. John Kerry, a Democrat from Massachusetts, was not discouraged about the fitful negotiations.

“My sense is we can get this done,” he told the AP as he visited the conference.

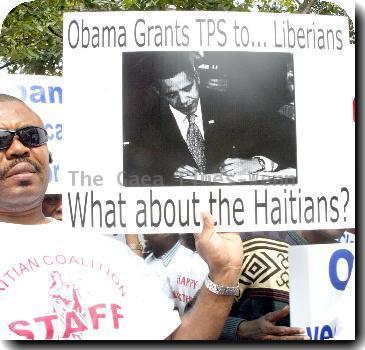

Hundreds of protesters marched on the suburban Bella Center, where lines of riot police waited in protective cordons. Some demonstrators said they wanted to take over the global conference and turn it into a “people’s assembly.” As they approached police lines, they were hit with pepper spray. TV pictures showed a man being pushed from a police van’s roof and struck with a baton by an officer.

Tens of thousands rallied in the Danish capital last weekend, demonstrating growing public awareness of the worldwide danger of ever-rising temperatures. Scientists say global warming will lead to the extinction of plant and animal species, the flooding of coastal areas from rising seas, more extreme weather, more drought and more widespread diseases.

The draft texts being debated behind closed doors hinge on four key issues, with negotiating views generally divided between rich nations and developing ones:

— Emissions. Industrialized nations are under pressure to cut back even more on emissions of carbon dioxide and other global-warming gases, while major developing countries such as China and India are being pressed to rein in emissions growth. Environmentalists and poorer nations say richer countries should reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent or more by 2020, compared with 1990 levels, to avoid serious climate damage. The EU has pledged 20 percent, and possibly 30 percent. The U.S. has offered only a 3 percent to 4 percent cut.

— Financing. Richer nations have discussed a “prompt-start” package of $10 billion a year for three years to help developing nations adjust to the impact of global warming and switch to clean energy. Developing nations want to see commitments by wealthy nations for years more of long-term climate aid financing. Expert studies say hundreds of billions of dollars will be needed each year, and the developing nations are trying to establish stable revenue sources, such as a global aviation tax.

— Monitoring. The U.S. and developed nations want some kind of international verification of emissions actions by developing nations. China, India and others are resisting what they consider potential intrusions on their sovereignty.

— Legal Form. For Europe, Japan and other developed nations, new, deeper emissions cuts will take the form of an extension of quotas under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. The U.S., which rejected Kyoto and wants to remain outside it, is likely to be included in a separate package that also deals with major developing countries. The level of legal obligation on each “track” may vary, particularly since the big developing countries — China and India — do not want to be bound by any international treaty to carry out their pledges of emission cuts. They prefer voluntary goals.

EDITOR’S NOTE — Find behind-the-scenes information, blog posts and discussion about the Copenhagen climate conference at www.facebook.com/theclimatepool, a Facebook page run by AP and an array of international news agencies. Follow coverage and blogging of the event on Twitter at: www.twitter.com/AP_ClimatePool

Tags: Asia, Barack Obama, China, Climate, Connie hedegaard, Copenhagen, Denmark, East Asia, Environmental Concerns, Environmental Laws And Regulations, Europe, Facebook, Government Regulations, Greater China, India, International Agreements, Japan, John Kerry, North America, Protests And Demonstrations, South Asia, United States, Western Europe