PROMISES, PROMISES: US threats to punish Sudan over human rights prove empty

By Desmond Butler, APTuesday, July 13, 2010

PROMISES, PROMISES: US fails to punish Sudan

WASHINGTON — The words of the Obama administration were unequivocal: Sudan must do more to fight terror and improve human rights. If it did, it would be rewarded. If not, it would be punished.

Nine months later, problems with Sudan have grown worse. Yet the administration has not clamped down. If anything, it has made small conciliatory gestures.

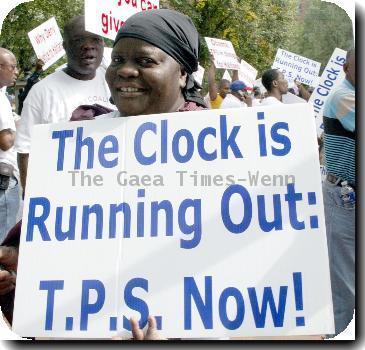

Activists say the backtracking sends a message that the United States is not serious about confronting Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, charged with genocide by an international court on Monday.

“They had a fine strategy. They just haven’t implemented it,” said Amir Osman, a senior director at the Save Darfur Coalition. “Nobody will take them seriously until they do what they said they would do.”

The White House denies it has abandoned the strict course it set. It says there have been signs of progress in Sudan despite a recent rise in violence in Darfur and a crackdown on opposition by the government.

Sudan poses many thorny problems for Washington. The United States has long accused it of sponsoring terrorism. The genocide charges against al-Bashir follow war crimes charges filed against him last year. Militias backed by his government are accused of slaughtering civilians in the Darfur region in a conflict that has killed an estimated 300,000 people.

The United States also is concerned about preserving a 2005 peace agreement from a separate conflict between the mostly Muslim north and predominantly animist and Christian south. Under the deal, the south is to hold a referendum in January in which it is likely to vote to secede. Details have not been worked out, however, and there are fears the vote could ignite another war.

U.S. officials have been divided about how to deal with Sudan. Some argue that only a tough line can end Sudan’s violence. Others, notably White House envoy Scott Gration, say it is critical to work with the government to ensure that any secession by the south occurs peacefully.

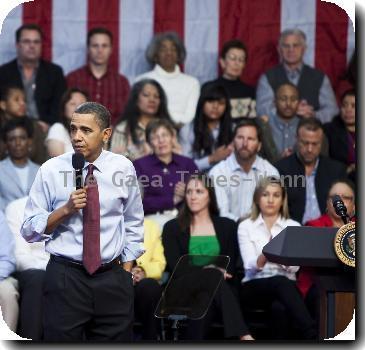

President Barack Obama settled on something of a compromise. On Oct. 19, his administration announced that the Sudanese government would be rewarded for making progress, but punished if it failed to do so.

It did not say what the punishments or rewards would be, but it explained how they would be determined. It planned to establish indicators by which changes in Sudan could be measured. The White House would regularly review the indicators, which would trigger the rewards or penalties.

“There will be no rewards for the status quo, no incentives without concrete and tangible progress,” said the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Susan Rice. “There will be significant consequences for parties that backslide or simply stand still. All parties will be held to account.”

Since then, there has been backsliding, as the administration has acknowledged. It issued a statement Friday, together with Norway and the United Kingdom, criticizing Sudan for worsening human rights violations throughout the country and for breaking cease-fires in Darfur, noting its use of aerial bombardment and the deployment of local militias.

Yet the U.S. has not punished Sudan. Instead, it has offered small incentives. The State Department recently expanded visa services for Sudanese citizens in its embassy in Khartoum. It also sent a low-level representative to al-Bashir’s inauguration.

Administration officials say Sudan is regularly discussed at high-level meetings. Officials say they use indicators to measure progress in Sudan, but have declined to say what those indicators are. Even a top lawmaker dealing with Africa issues, Rep. Donald Payne, D-N.J., said he has difficulty getting information.

“I haven’t heard what the benchmarks are or what specifically will be done if they are not met,” said Payne, chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Africa subcommittee.

The White House’s top Africa policy adviser, Michelle Gavin, said the administration never intended to have specific metrics that would automatically prompt a reaction. Instead, the White House would use the indicators to continually reassess its policy.

“The idea of some kind of one-for-one scenario where for each indicator we look at we deploy some corresponding carrot or stick is an oversimplification — no policy could function that mechanistically,” she said.

Gavin and other administration officials point to signs of progress, including Sudan’s improved relations with neighboring Chad. They say the recent elections were important, even though they were flawed. They also believe Khartoum is prepared to let go of the south and has taken steps to facilitate the referendum. Last week, government officials began talks with southern leaders on how to ensure a smooth transition.

But John Prendergast, head of an anti-genocide program at the Center for American Progress, a think tank close to the White House, said the Sudanese government has stalled on key aspects of setting up the referendum and has yet to agree on how to demarcate the border and share oil revenue. He said the United States may have sent the wrong signal by giving Sudan a pass on other issues.

“If the parties, particularly the ruling party, do not understand that there will be real consequences for a return to war, and real benefits for peace in the country,” he said, “then the U.S. has lost its biggest point of influence in the effort to avert the worst-case scenario.”

Tags: Africa, Barack Obama, District Of Columbia, Genocides, Khartoum, Middle East, North Africa, North America, Sudan, United States, Washington