New China-Tibet talks highlight slight shift in Beijing’s policies toward western regions

By Christopher Bodeen, APFriday, January 29, 2010

New China-Tibet talks show slight policy shift

BEIJING — New talks with the Dalai Lama’s envoys are highlighting subtle shifts in China’s approach to its restive, riot-scarred western regions of Tibet and Xinjiang.

The meetings with representatives of the exiled spiritual leader, scheduled to start Saturday in Beijing, signal a renewed willingness to re-engage with Tibet’s self-declared government-in-exile after a 15-month freeze in direct contact.

They follow a high-level Communist Party conference on Tibet that emphasized raising rural livelihoods, an apparent acknowledgment that decades of investment in industry and infrastructure have failed to endear the region’s herders and farmers to Chinese rule.

A similar gathering on Xinjiang policy is planned for later this year, with the Communist Party’s chief for law and order saying new programs are needed to react to changes in the predominantly Muslim region.

Riots that broke out in Tibet in 2008 marked the region’s worst ethnic violence in decades, prompting China to seal it off and pour in troops. Bloodier violence in Xinjiang last summer left almost 200 people dead. A security clampdown that included cutting access to the Internet, text messaging and international calls, remains largely in place.

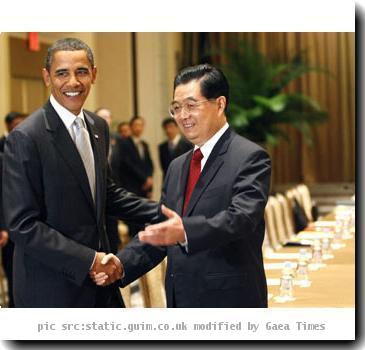

In the wake of the unrest, China dispatched government scholars and bureaucrats to study conditions on the ground and draft recommendations. Last week’s Tibet conference, attended by President Hu Jintao and other top officials, afforded the opportunity to air the results and introduce subtle shifts in priorities.

While more rhetorical and procedural than substantive, the moves have some observers of Chinese politics seeing at least the possibility of more nuanced thinking creeping in.

“We do have these episodes of hope from time to time,” said Michael C. Davis, an expert on Tibet at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The region has been a source of controversy for decades, since Beijing sent troops to occupy Tibet following the 1949 communist revolution. It insists the region has been part of Chinese territory for centuries, a claim disputed by many Tibetans.

A failed uprising in 1959 led the Dalai Lama to flee into exile in India.

Beijing has accused him of trying to split the country. The Dalai Lama has repeatedly denied the accusations and says he seeks only a high level of autonomy for Tibet.

The Tibet conference avoided the issue of autonomy, but called for raising rural incomes in the region to the level of the rest of China by the end of the decade, while boosting funding for ethnic Tibetan areas in neighboring provinces that also witnessed anti-government protests in 2008.

The strategies reflect China’s insistence that problems out west are economic in origin rather than religious or ethnically based, but also that funding needs to be redirected toward improving livelihoods and not simply infrastructure.

China has spent 140 billion yuan ($20 billion) on development in Tibet since 2001, but critics complain much of the money has gone to projects that benefit Chinese companies and migrants, while fueling resentment of Beijing’s rule among poor Tibetans.

Documents issued at the conference were relatively free of the usual invective against the Dalai Lama and other “splittists,” creating a less politically charged atmosphere.

Analysts have also pointed to comments by one Chinese delegate to the Tibet talks, Zhu Weiqun, characterizing the Dalai Lama’s claims not to be seeking independence as “good, though not enough.”

Though Zhu said further clarification was needed from the Dalai Lama, his remarks were a departure from Beijing’s usual blanket dismissals of the 75-year-old Buddhist leader’s calls for substantial autonomy under Chinese rule.

The latest talks are the ninth round in a process that began in 2002. Neither side has revealed details about the agenda and expectations for progress are low.

Beijing insists that talks only address the return of the Dalai Lama, rejecting proposals raised by the exiles at previous talks for greater autonomy.

“I cannot see what the recent round of negotiation can achieve in concrete terms,” said Dibyesh Anand, professor of international relations at London’s Westminster University.

Speculation over Tibet policy has also raised questions about Beijing’s approach to Xinjiang, which is also led by a hardline Chinese Communist Party leader who pledges often and publicly to crush all dissent.

The goal of that conference, the date of which has not been announced, is to “make a plan to support the development of Xinjiang and promote the long-term stability and prosperity,” according to state broadcaster CCTV.

While offering no prospect of political dialogue, the Xinjiang meeting could introduce similar measures to improve economic opportunities for the native population, the Uighur ethnic group, whose incomes lag far behind the Han Chinese majority.

Despite the moves, analysts who study Tibet and Xinjiang are skeptical of any major changes in Chinese policy.

China says its crackdown on Uighur separatists is part of the global campaign against terrorism. Such claims are bolstered by occasional attacks in the region and recent reports that 13 Chinese Uighurs were among those killed in a U.S. missile strike in Afghanistan.

On Tibet, meanwhile, Beijing finds itself under little pressure to change its approach or make concessions over Tibet. Still, Beijing may see engagement with the Dalai Lama’s envoys as useful for allaying international criticism.

“As in the past, such talks assuage certain international concern, but don’t derail China’s actual policies in Tibet, said China scholar Elliot Sperling at Indiana University.