Psychiatrists propose changes in how doctors diagnose and name mental disorders

By Lauran Neergaard, APWednesday, February 10, 2010

Changes proposed in how psychiatrists diagnose

WASHINGTON — Don’t say “mental retardation” — the new term is “intellectual disability.” No more diagnoses of Asperger’s syndrome — call it a mild version of autism instead. And while “behavioral addictions” will be new to doctors’ dictionaries, “Internet addiction” didn’t make the cut.

The American Psychiatric Association is proposing major changes Wednesday to its diagnostic bible, the manual that doctors, insurers and scientists use in deciding what’s officially a mental disorder and what symptoms to treat. In a new twist, it is seeking feedback via the Internet from both psychiatrists and the general public about whether the changes will be helpful before finalizing them.

The manual suggests some new diagnoses. Gambling so far is the lone identified behavioral addiction, but in the new category of learning disabilities are problems with both reading and math. Also new is binge eating, distinct from bulimia because the binge eaters don’t purge.

Sure to generate debate, the draft also proposes diagnosing people as being at high risk of developing some serious mental disorders — such as dementia or schizophrenia — based on early symptoms, even though there’s no way to know who will worsen into full-blown illness. It’s a category the psychiatrist group’s own leaders say must be used with caution, as scientists don’t yet have treatments to lower that risk but also don’t want to miss people on the cusp of needing care.

Another change: The draft sets scales to estimate both adults and teens most at risk of suicide, stressing that suicide occurs with numerous mental illnesses, not just depression.

But overall the manual’s biggest changes eliminate diagnoses that it contends are essentially subtypes of broader illnesses — and urge doctors to concentrate more on the severity of their patients’ symptoms. Thus the draft sets “autism spectrum disorders” as the diagnosis that encompasses a full range of autistic brain conditions — from mild social impairment to more severe autism’s lack of eye contact, repetitive behavior and poor communication — instead of differentiating between the terms autism, Asperger’s or “pervasive developmental disorder” as doctors do today.

The psychiatric group expects that overarching change could actually lower the numbers of people thought to suffer from mental disorders.

“Is someone really a patient, or just meets some criteria like trouble sleeping?” APA President Dr. Alan Schatzberg, a Stanford University psychiatry professor, told The Associated Press. “It’s really important for us as a field to try not to overdiagnose.”

Psychiatry has been accused of overdiagnosis in recent years as prescriptions for antidepressants, stimulants and other medications have soared. So the update of this manual called the DSM-5 — the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition — has been anxiously awaited. It’s the first update since 1994, and brain research during that time period has soared. That work is key to give scientists new insight into mental disorders with underlying causes that often are a mystery and that cannot be diagnosed with, say, a blood test or X-ray.

“The field is still trying to organize valid diagnostic categories. It’s honest to re-look at what the science says and doesn’t say periodically,” said Ken Duckworth, medical director for the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, which was gearing up to evaluate the draft.

The draft manual, posted at www.DSM5.org, is up for public debate through April, and it’s expected to be lively. Among the autism community especially, terminology is considered key to describing a set of poorly understood conditions. People with Asperger’s syndrome, for instance, tend to function poorly socially but be high-achieving academically and verbally, while verbal problems are often a feature of other forms of autism.

“It’s really important to recognize that diagnostic labels very much can be a part of one’s identity,” said Geri Dawson of the advocacy group Autism Speaks, which plans to take no stand on the autism revisions. “People will have an emotional reaction to this.”

Liane Holliday Willey, an author of books about Asperger’s who also has the condition, said in an e-mail that school autism services often are geared to help lower-functioning children.

“I cannot fathom how anyone could even imagine they are one and the same,” she wrote. “If I had put my daughter who has a high IQ and solid verbal skills in the autism program, her self-esteem, intelligence and academic progress would have shut down.”

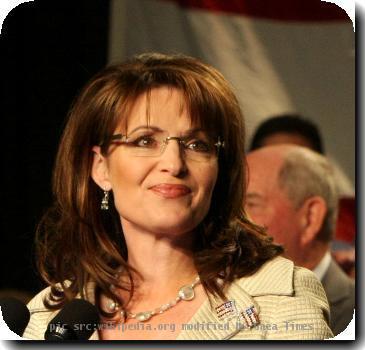

Terminology also reflects cultural sensitivities. Most patient-advocacy groups already have adopted the term “intellectual disability” in place of “mental retardation.” Just this month, the White House chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, drew criticism from former GOP vice presidential nominee Sarah Palin and others for using the word “retarded” to describe some activists whose tactics he questioned. He later apologized.

AP Medical Writer Lindsey Tanner in Chicago contributed to this report.

Tags: Developmental Disorders, Diagnosis And Treatment, Diseases And Conditions, Geography, North America, Political Organizations, Sarah palin, Special Interest Groups, United States, Washington